Responding to violence

I have been fortunate not to have much violence directly inflicted on me. But I live in a violent world.

I have studied violence academically, and worked with victims/survivors of violence. I have hit others and been hit. My immediate family has been affected by a domestic violence murder. I have been closely involved with a large mass murder. I live in a city where there are weekly shootings. I watch the news, which emphasizes violent crime and war. I grew up with violent stories, from westerns to WW2 dramas to cop shows to comic books. I played games with pretend and real violence. I live in a culture which in ideology if not always in practice valorizes those in violent professions (military and police). I live on land taken from others, I enjoy the privilege of labor taken from others in prior and current generations, and my tax dollars support killing and torture. My DNA - like everyone's - comes from history's victors as well as its victims.

All this is a roundabout way of saying that I - like everyone I know - is no stranger to the subject.

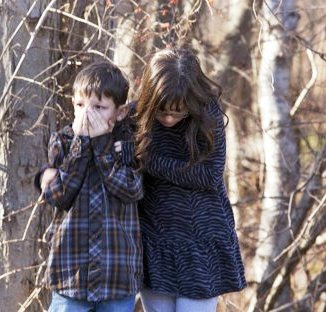

But when I am true to myself, when I encounter an outrage like today's, or like the drones that descend out of the sky to kill enemies and bystanders alike, or like the bullets which fly on MLK Drive and Ocean Avenue, I know that this defies understanding. How can you truly engage with the horror of innocents murdered, with the terror which the adults and children must have felt when a killer came to their school?

We certainly have a responsibility to try and understand the mechanisms of violence so that we might interrupt them, and heal them. Turning swords into plowshares is our vocation.

But however much you can describe the facts about violence, it is in a certain sense untouchable, like a black hole. There is a great rupture in the fabric of God's kingdom when murder is plotted and carried out. All explanations must pause before this reality, that evil is senseless, that it is the antithesis of the power of life, which animates and sustains us.

I think that the Jesus of the gospels - himself a torture and murder victim - realized we cannot do much to engage with evil on its terms. We can instead oppose it best by refusing to feed it: by loving our enemies, by returning good for evil, by praying for the deliverance of those in bondage, and by living a life steeped in forgiveness, God's and ours.

The most unusual mass shooting of recent years, to my mind, was the story which did not seize the national imagination quite as much as Columbine or Aurora or Newtown. It was a school shooting. On October 2, 2006, a gunman entered the West Nickel Mines School, a one-room schoolhouse in the Old Order Amish community of Lancaster, PA. There he shot ten girls (aged 6-13), killing five before taking his own life.

Of course the remarkable, radical, unimaginable and unbelievable thing is the way the community, including the victims and their family members immediately began to enact compassion and forgiveness for the murderer and his family. Their community, in the midst of pain and knowing how hard it would be, took Jesus' words as a commandment, and tried to live out the necessity of forgiveness.

This is foreign to our experience of the way things "should" work, and our perception of the difficulty (impossibility?) of healing from violence. There is no question that forgiveness is hard, very hard for us to do. We can see this in the way we can hold seemingly small grudges for years.

But those who forgive - even as they struggle to practice it fully - immediately shed many of the burdens and dangers of engaging with evil. They are instead free to engage with grief, with hope, and with the love which the killer was not able to know, nor to erase.

Grace and peace to you.

I have studied violence academically, and worked with victims/survivors of violence. I have hit others and been hit. My immediate family has been affected by a domestic violence murder. I have been closely involved with a large mass murder. I live in a city where there are weekly shootings. I watch the news, which emphasizes violent crime and war. I grew up with violent stories, from westerns to WW2 dramas to cop shows to comic books. I played games with pretend and real violence. I live in a culture which in ideology if not always in practice valorizes those in violent professions (military and police). I live on land taken from others, I enjoy the privilege of labor taken from others in prior and current generations, and my tax dollars support killing and torture. My DNA - like everyone's - comes from history's victors as well as its victims.

All this is a roundabout way of saying that I - like everyone I know - is no stranger to the subject.

But when I am true to myself, when I encounter an outrage like today's, or like the drones that descend out of the sky to kill enemies and bystanders alike, or like the bullets which fly on MLK Drive and Ocean Avenue, I know that this defies understanding. How can you truly engage with the horror of innocents murdered, with the terror which the adults and children must have felt when a killer came to their school?

We certainly have a responsibility to try and understand the mechanisms of violence so that we might interrupt them, and heal them. Turning swords into plowshares is our vocation.

But however much you can describe the facts about violence, it is in a certain sense untouchable, like a black hole. There is a great rupture in the fabric of God's kingdom when murder is plotted and carried out. All explanations must pause before this reality, that evil is senseless, that it is the antithesis of the power of life, which animates and sustains us.

I think that the Jesus of the gospels - himself a torture and murder victim - realized we cannot do much to engage with evil on its terms. We can instead oppose it best by refusing to feed it: by loving our enemies, by returning good for evil, by praying for the deliverance of those in bondage, and by living a life steeped in forgiveness, God's and ours.

The most unusual mass shooting of recent years, to my mind, was the story which did not seize the national imagination quite as much as Columbine or Aurora or Newtown. It was a school shooting. On October 2, 2006, a gunman entered the West Nickel Mines School, a one-room schoolhouse in the Old Order Amish community of Lancaster, PA. There he shot ten girls (aged 6-13), killing five before taking his own life.

Of course the remarkable, radical, unimaginable and unbelievable thing is the way the community, including the victims and their family members immediately began to enact compassion and forgiveness for the murderer and his family. Their community, in the midst of pain and knowing how hard it would be, took Jesus' words as a commandment, and tried to live out the necessity of forgiveness.

This is foreign to our experience of the way things "should" work, and our perception of the difficulty (impossibility?) of healing from violence. There is no question that forgiveness is hard, very hard for us to do. We can see this in the way we can hold seemingly small grudges for years.

But those who forgive - even as they struggle to practice it fully - immediately shed many of the burdens and dangers of engaging with evil. They are instead free to engage with grief, with hope, and with the love which the killer was not able to know, nor to erase.

Grace and peace to you.

Comments